The time I met show-business legend George Jessel

While I have worked for four presidents in my forty-five year career in American politics, meeting George Jessel remains one of the greatest thrills of my life.

In 1980, I was serving as the Northeastern Regional Political Director for Governor Ronald Reagan’s campaign for President, with responsibility for his campaign efforts in New York, New Jersey, and my native Connecticut. Our New York campaign headquarters was in an elegant but rundown brownstone mansion on West 52nd Street, next to the storied “21 Club.”

I was shocked one day to see old-time vaudevillian George Jessel enter the building and ask to see the “top man.” Jessel, then in his late 80’s, has lunched at the “21 Club” and someone told him that Reagan’s headquarters was next door.

Jessel was affectionately known by his nickname, “The Toastmaster General of the United States” due to the number of times he performed as master of ceremonies at various special events and eulogies. By this time in his life, Jessel was wearing a military-style officer’s hat, as well as various medals and awards given to him by Presidents, Governors, and Kings.

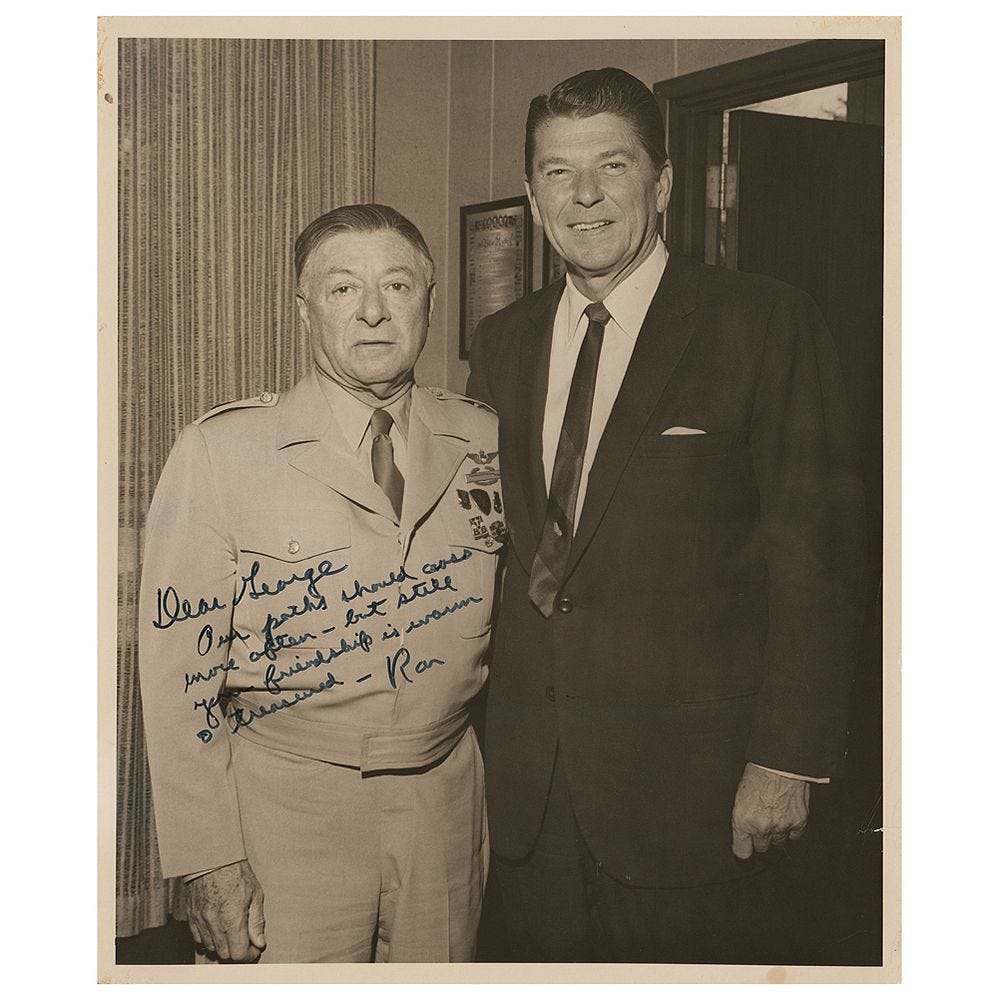

Coincidentally, there was a New York Times photographer in the office shooting photos of our headquarters for an piece on Reagan’s coming sweep of delegates in the upcoming New York state Republican primary. That photographer captured my prized photograph with this show-business legend.

George Jessel was a “man about town” during the roaring Twenties, and remained an icon in show business through the rest of his very entertaining life in the entertainment industry. As one of the most prolific multi-talented comedic performers in America, his success as an actor, singer, songwriter, author, director, and producer is still revered in Hollywood to this day.

He frequented the most fashionable parties and hob-knobbed with the most successful entertainers, business owners and athletes – and even Presidents. Ronald Reagan was one of his closest friends, in addition to famous pals like Milton Berle, Danny Kaye, Bob Hope, Eddie Cantor, Jack Benny, George Burns, Louis B. Mayer (founder of MGM) and many other people who held him in the highest esteem.

George Jessel was born in Harlem, NY in 1898 to a Jewish family of entertainers. His mother sold tickets at a local theater and his father was a traveling salesman, auctioneer and unsuccessful playwright who forbade George from performing in public due to his own failures in show business, but his mother encouraged it.

During an interview where he was asked how he got into show business, Jessel said, “My father didn’t want me in the theater. He hadn’t done well there and grew to hate it, but he died when I was 10 years old, and I went to live with my mother’s father. He was a tailor, and he liked to hear me singing around the shop. Before long I was singing at lodge meetings — and after that, things sort of happened.”

While working at The Imperial Theater, his mother noticed that the patrons were often bored while they waited for the show to start so she helped George and two other ushers develop an act that would entertain the audience before the show began. They called themselves “The Imperial Trio.”

The trio became an overnight sensation, but the standout was George Jessel. Starmaker, Gus Edwards, who also discovered Groucho Marx, discovered George’s talent as soon as he saw it and hired him to perform with his traveling vaudeville troupe, Kid Kabaret, with Eddie Cantor – at the age of 11.

In 1911, at the age of 13, Jessel was so well recognized as a skilled actor that Thomas Edison asked for his help while experimenting with talking movies. He toured the British Isles in 1915 and was known as the “Boy Monologist” in vaudeville by 1917, but after outgrowing his role as a child in Kid Kanaret, George began acting in Broadway plays, movies, writing music, producing television shows and doing stand-up comedy routines where he developed an act in which he conducted an imaginary telephone conversation with his mother, which became legendary. The phone calls remained in his act even after he left vaudeville, and he wrote a book about if called “Hello Momma.”

He recorded his hit musical recording “Oh How I Laugh When I Think How I Cried About You.” In 1920, at the age of only 21.

The Jazz Singer was first developed as a Broadway play in 1925, and then produced into a featured film in 1927. It’s about a Jewish entertainer who wants to be a famous jazz singer, but his father won’t allow it. This was something Jessel could relate to since his own father was against him being in show business. The lead character of the play was performed, in blackface, by Charles Jessel, and he was the first choice of Hollywood studio executives to be the star of the movie, which was based on the play that Jessel was performing in, but due to financial and production issues, Al Jolson got the part, partly due to him funding the movie – which gave Al Jolson the distinction of being in the first full length “talking” movie ever made. Jessel said the biggest regret of his life was to being in that movie.

The story is a bit more complicated than that. Although Jessel and Jolson were actually rooming together at the time in New York, Jolson surreptitiously slipped town to travel to Hollywood to meet secretly with Jack Warner, of Warner Brothers Pictures. The Warner brothers were on hard financial times, but had developed the technology for “talking pictures.” In reality, what they had was the ability to insert both music and limited recorded dialogue into what were then still silent movies.

Jolson, on the other hand, had been a major star of Broadway and was actually the first Broadway star to take a full-blown musical on the road. Taking his various Broadway hits to venues in Chicago, Detroit, St. Louis, and other major U.S. cities. Jolson had also wisely invested his entertainment industry earnings in Southern California real estate and was by that time an exceedingly wealthy man.

Unable to meet Jolson’s financial demands, which were only increased by the uncertainty and perceived risk of “talking pictures,” the Warner brothers ultimately gave 50% of the stock in their company to Jolson who was even then known as the “The World’s Greatest Entertainer.” Jolson emerged with the starring role in The Jazz Singer—leaving his best friend Georgie Jessel to read about it in the trade publication Variety.

George continued staring in movies, acting on Broadway, writing music and producing plays, for decades, earning him recognition as one the greatest showmen of all time. He estimated that he traveled about 8,500 miles a week, 40 weeks a year, to about 200 different gatherings each year. He was one of the most prolific musical producers of the 40’s, and also starred in the George Jessel radio and TV Shows during the 1950’s while produced 24 films for 20th Century Fox by the 1960’s, and all while writing a large number of best-selling songs.

When he was not performing or acting for an audience, he was entertaining U.S Soldiers serving in World Wars I and II, Korea and Vietnam – or championing Jewish causes.

George liked the ladies. He especially liked them young. His first marriage to Florence Courtney ended badly when she divorced him on the grounds of cruelty and his second marriage was also mired in scandal after he broke into his ex-wife’s house and shot at her new boyfriend. He has had multiple affairs and children out of wedlock but one of his biggest scandals was marrying 16-year-old Lois Andrews when he was 42 years old. They had a daughter before divorcing two years later. But his biggest sexual scandal occurred in 1964 when he groped Shirley Temple. According to Temple, when she was 35 years old, he invited her to his office under the guise of discussing a recent role. During their meeting, Jessel put an arm around her while taking off his pants. He then groped Temple’s breasts. She fought off his advances by kicking him in the groin and fleeing.

One of his most famous liaisons with a lady happened in 1934, when segregation in New York was widespread, and George Jessel had an idea that he thought would get a few laughs and make a point about the silliness of segregation. He hired a limousine, put on a nice suit, black hat and cane and drove to Harlem where Lena Horne was performing at the Cotton Club. He approached her and said, “Hello, my beautiful! You look beautiful, you’re beautiful, you sun-tanned beautiful thing. Is the show over or you got another show? We’ll go out, we’ll have a midnight snack.” She agreed and they left for the Stork Club, which was one of the most racist clubs in the city.

American columnist Walter Winchell said, “The Stork Club discriminates against everybody. White, black, and pink. The Stork bars all kinds of people for all kinds of reasons. But if your skin is green and you’re rich and famous or you’re syndicated, you’ll be welcome at the club.”

Jessel walked up to the Stork Club, with Lena Horne on his side, but they were stopped by a bodyguard before they could enter.

They were told to wait as he checked with the owner of the Stork Club, Sherman Billingsley, to see if it was OK to let them in. After checking with the owner, the bouncer came back and asked Jessel who made his reservation, and Jessel responded – “Abraham Lincoln, you son-of-a-bitch.”

George Jessel was an entertainer until the day he died, in 1981, at the age of 83. His last show was two weeks before his death. When asked why he was still working into his 80’s, Jessel responded, “Why not? What else should I do with my time — collect stamps?”

While I have worked for four presidents in my forty-five year career in American politics, meeting George Jessel remains one of the greatest thrills of my life.

Good story